A revised map of Tranquility

June 13, 2016

Space Opera Politics: post-conflict politics in the Human Legion Pt. 2

June 23, 2016Back in the pulp science fiction of the 1930s and 40s, galactic politics in these earliest space operas were usually easy to grasp. You had space empires, space federations and sometimes space republics. (People must have had a lot of space in those days). Whether the person at the top of the tree was a queen, emperor, or president made little practical difference.

And how were such sprawling empires held together? Well, naturally, with quasi-military or feudal setups, often supported by a pernickety bureaucracy that readers were invited to ridicule.

Empires competed in a kind of military-political Olympic Games where the winners were determined not by the country with the most gold medals, but the empire with the most planets and star systems. In the constant struggle to expand your empire, there were three common mechanisms of advancement:

- Conquering planets held by the other side.

- Merging in smaller empires by alliance, marriage or peace treaty.

- Planting and nurturing your own colonies.

In reality, if you read stories of that time, then you will know the politics of mid-20th-century space opera was not always as simple as I’ve described. As the decades rolled by toward the present day, the complexity and diversity of space opera politics has mushroomed. And yet even today, some commentators still insist that space opera is inherently right-wing, even if some of its authors are not right-wing.

You won’t normally hear me talk about contemporary politics on humanlegion.com because I prefer science fiction that subtly encourages its readers to see the world – with its real people and its real problems — through a fresh perspective. And it can do this precisely because it breaks free of the mental shackles of forcing everything through the prism of contemporary politics and other contemporary issues.

Science fiction writers can choose to leave contemporary issues behind, as if the universe has moved on and passed them by (nothing wrong with a good dose of escapism), or they can use the unique vantage point of a fictional universe to paint a fresh picture of contemporary issues using new light. The trick to the second approach is to not do so overtly (as Iain M. Banks often described his approach to writing his post-scarcity ‘left-wing space operas’ in his ‘Culture’ novels).

At this point I’m tempted to lay into the bad science fiction writers (and commentators) of all political philosophies who lack the imagination to write stories free from clumsy references to today’s political figures, and today’s trending topics. However, there’s more than enough tribalism in science fiction already without me adding to it.

Left-wing vs. right-wing. Progressive vs. reactionary. Puppies vs. anti-puppies. People who agree with me vs. everyone who dares to disagree. Simplistic ‘us and them’ abounds and I just don’t buy into that way of thinking. I’ve always found it ridiculous to believe that an individual human being’s political and philosophical view of the world is a scalar quantity – something you can encompass with a single number.

“Have you heard about the new neighbors? CitFacts says their politics average 27.3. It’s absolutely disgraceful! I could never bring myself to talk with anyone who scored above 15.”

“You’re right. They’re way beyond unpleasant, dear. Something will have to be done…”

It’s my firm belief that real people are far too complicated to be summarized by a single number, and that’s why I reject labeling someone as this-wing or that-wing and leaving it at that, as if doing so is everything you need to understand a human being. Besides, authors who believe they can describe someone as a simple number on a political scale write unconvincing characters, and that leads to bad books, and if I wrote bad books then I wouldn’t get paid.

Nonetheless, much as I distrust describing anything as left- or right-wing (including myself), the reason I bring this up is because with space opera’s tendency to focus on empires, aggressive wars, and colonization, I can understand where concerns about an inherently right-wing bias would come from: those who describe themselves as left-wing regard such aggressive attitudes as belonging exclusively to the right.

“Your Majesty, let’s conquer the long-inhabited planets of our neighboring star system because… well, because our military is stronger than theirs and because we can. Afterwards, we can plant our colonists and ruthlessly exploit their resources to feed our own industries.”

“Sounds like a plan, Admiral. We’ll invade next Tuesday, right after the ball game.”

That kind of exploitative attitude doesn’t wash with real readers in Western liberal democracies, whichever party they vote for, nor should it. Which is why if there’s fighting to be done, it’s so much easier on the reader’s morality to have the protagonists be on the good side.

For example:

- “Earth and her fledging colonies are attacked by aliens.” It’s a popular theme, and you can see why. It’s easy to identify the good guys.

- “An oppressed minority rises up against a totalitarian regime.” That basically sums up Star Wars, and that franchise seems popular. We know who the good guys are, so let’s not worry about what we do if we win. Which brings me to the Human Legion.

Freedom can be won is the tagline of the Human Legion series, and when Arun McEwan and his comrades first dare to dream this, the idea of freedom seems so impossibly distant that they give no thought to what shape that freedom might take. Just surviving until the next day is plenty enough to think about for the time being.

But by the fifth book in the series (War Against the White Knights, published March 2016) this question about what might come after the war is something they can no longer dodge. The answer is uncertain, partially because there is still a lot of fighting to be done, but already it is clear that it will be no utopia. They have no choice but to address the political implications of what they have done, and what they have un-done.

You can see one of Book 5’s Infopedia sections describing the fledgling Human Autonomous Region here. Things will get more complex in the sixth book when the action finally comes home to Earth itself.

An empire that is torn down leaves power vacuums. If there aren’t stable civilian institutions or an expectation of the rule of law, then they need not only to be established but to bed down too. That takes a long time and a lot of pain. The difficulty in this bedding down period is the reason I’m going to vote in a referendum this week to determine whether my country should stay in the European Union. History gives us many other examples.

Take the early United States of America after the War of Independence. It’s easy for someone like me, who isn’t American, to look at the US today, see a (more or less) single unified political entity stretching across North America, and assume that such an outcome was inevitable since 1783, a Manifest Destiny if you like. The reality, of course, was often a fractious and uneasy alliance of states, cultures, peoples and philosophies that sporadically threatened to break apart all the way until 1861, when it finally did just that.

The area where the Human Legion has taken administrative control, the Human Autonomous Region, is closer to the USA of 1800 than that of 2016. It’s new, bursting with potential, but not fully formed; there’s a lot that’s good about it, and a lot that’s not. We don’t know where it will end up, but we can be sure it will be a bumpy ride.

Perhaps a more pertinent example is the chaos of Central and Eastern Europe in the aftermath of the First World War: rebellions, coups, the rise of thuggish fascism and equally thuggish Bolshevism, hyperinflation, all-out war between Poland and the Soviet Union, and power vacuums that led to political instability such as the disputes over control of the city of Fiume, which led to its occupation by an Italian poet-adventurer. In the real world, it was precisely this chaos that led to the unexpected significance of the Czechoslovak Legion, which is the inspiration for the Human Legion. Even after the guns fall silent, and the war has ended, there is still much to be done before we can say that freedom has been won.

And those guns won’t stay silent for long.

I’ll talk more about the post-war galaxy in part two, when I’ll connect Revenge Squad and the Human Legion to both the real-life destruction horizon in the colony where I grew up, and to smiley sun faces. Don’t know what a destruction horizon is? Stay tuned to find out.

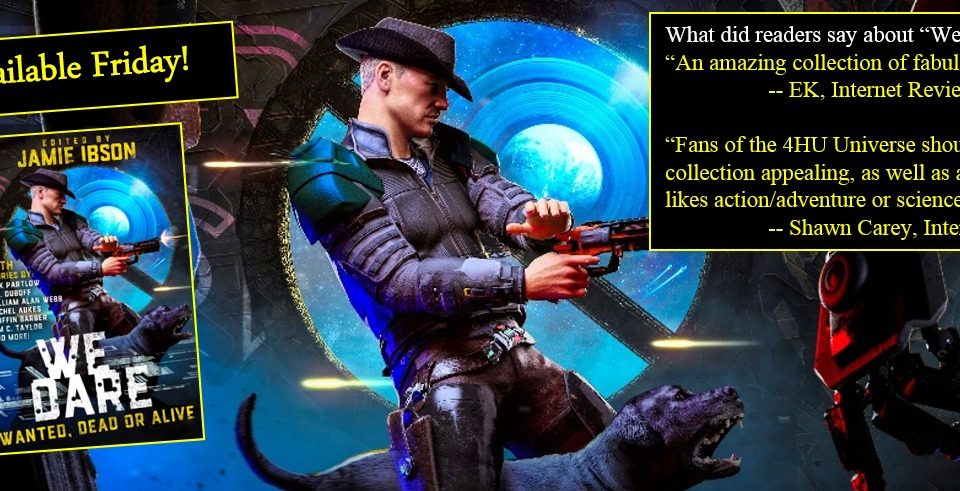

Click on the image and join the legion by the end of June for a chance to win a signed audiobook on CD.

5 Comments

Sounds interesting, can’t wait for part two! Dang that Industrial Military Complex!! (shakes fist at the sky)

Makes for good villains amongst some people. Part two coming up very soon…

I am just a simple ordinary guy who has not progressed from reading and enjoying books since a child. Many years ago I was surprised when my children came home from school talking about the political implications of “Gulliver’s Travels” which to me was just a children’s story. Now I am being educated in the complexity of the reasoning behind the story plots in Space Opera. I am now conscious that in deciding to write a series of books, like the Human Legion, an author must work out how the scenario develops and the consequences of all actions in the series before starting to write the first book. I find it difficult just to remember the names of the characters from chapter to chapter, how an author keeps track of them and what they have done is beyond my comprehension. Now we find that it is obvious to an author of Space Opera that to remove a dictator or government results in a need to fill the power vacuum and establish a rule of law to avoid chaos. The consequences of the action have to be worked out and plans made to fill the power vacuum agreed before waging war, or writing the books. If it is so obvious, then it beggars belief that our leaders have authorised military action many times then wonder why they have lost the peace. Maybe our governments should hire authors of Space Opera and obtain their approval before embarking on military adventures. You are doing a wonderful job Tim.

I definitely think that a lot of these stories were just that, stories, until someone came along afterwards. Most authors are trying to entertain, anything extra is pure happenstance.

I’d love to hire myself out if the job came with a gold-plated government pension. If not then I’ll have to decline. These stories don’t write themselves, you know 🙂